The Economic Problem

Merriam Webster defines economics as “a social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services,” which is quite a complicated definition. For our purposes, just think of it this way: there are unlimited wants in the world, but limited resources. Economics is the study of how to best meet these wants with our given resources. Fundamentally, this subject depends on the concept of scarcity – the idea that we don’t have enough resources in the world to satisfy all productive uses. Economists often refer to this dilemma as “the economic problem.”

To start, we must recognize that individuals want to maximize their utility, the overall enjoyment gained from consuming goods and services. Firms, on the other hand, aim to maximize profit; in economics, we have an entirely different understanding of what profit is than in, say, finance. But we’ll talk about that later. Moreover, when we’re studying the economic problem, we’re essentially trying to figure out which choices (alternatives) are most advantageous with the given constraints (scarcity).

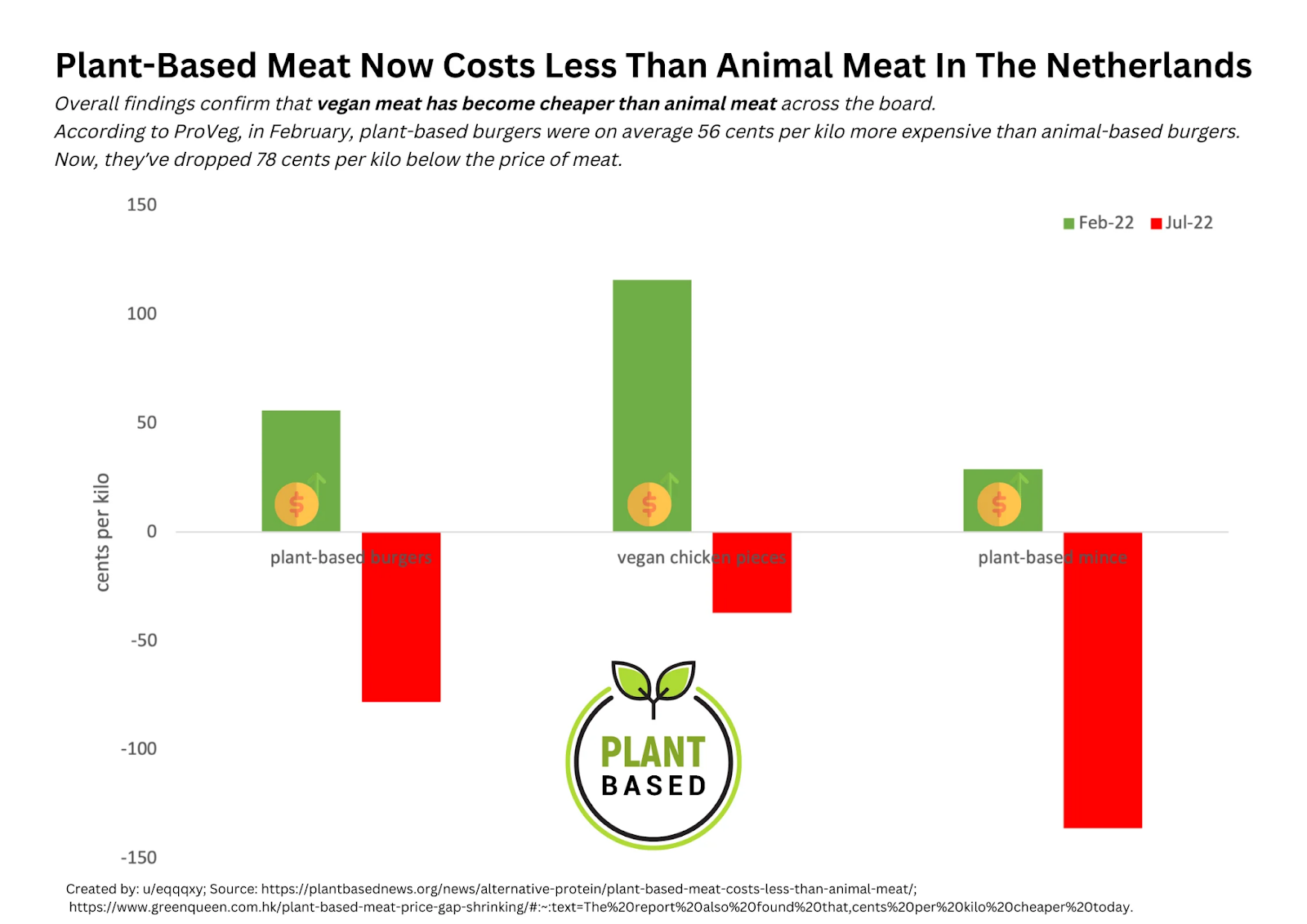

Since this course is about MICROeconomics, we’ll be focusing on decisions made by individuals and firms in SPECIFIC markets, as well as the consequences of those decisions. Macroeconomics examines ALL individuals and firms, as well as BROAD economic performance, and we won’t be covering it in this course. To illustrate the difference, here’s an example of a question in microeconomics: what impact would a tax on meat consumption have on the plant-based alternatives market?

Source: Reddit

Let’s quickly talk about some important terms to be aware of before diving into the course. First, a normative statement is one that carries opinion; it cannot be proven true or false by testing it against real-world data. Here’s an example: “football players are overpaid.” A positive statement is testable and simply tests the facts. Here’s an example: “Joe Burrow makes $55 million a year.”

Opportunity cost is arguably one of the most important terms in economics. It indicates the best alternative use of resources. Let’s look at another example: Tom has two choices of what to do tonight. He can either go to an Ed Sheeran concert or study for his math test tomorrow. If he chooses to go to the concert, his opportunity cost is whatever impact that not studying for the test has on his grade. Importantly, though, opportunity cost only considers the next best option, not every potential option. Every possible alternative use of Tom’s time does not sum up to make the opportunity cost, just whatever he would have done if he didn’t go to the concert, which in this case is studying.

Now, let’s discuss the law of diminishing returns. It states that, the more we do something, the less we gain each time. You’ve probably experienced this in your own life: the 60th Oreo you eat in one sitting probably doesn’t taste as good as the 1st one. Another example is with studying; the first hour you study for a test probably raises your ultimate grade more than the 7th hour spent. This is all closely tied to marginal analysis, which looks at what happens when we produce or consume just one additional unit of something. Make sure you understand both this concept and opportunity cost before moving on to the next page.