Price Elasticity of Demand

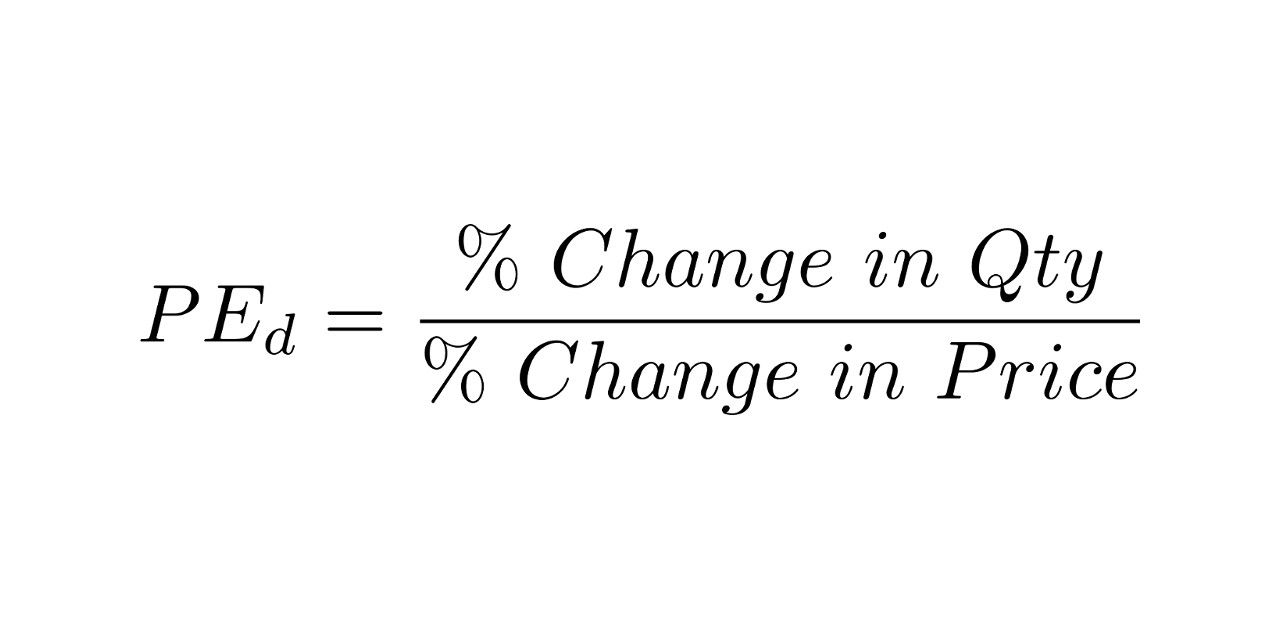

Let’s talk about elasticity, which is just a measure of sensitivity. Price elasticity of demand answers the question: how much does demand change when price changes? The formula for price elasticity of demand is the absolute value of the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. That sounds like a lot, but it’s just this:

Source: Investopedia

Importantly, calculating price elasticity is directional. The price elasticity of demand from point A to B on a graph is generally different from that of point B to A.

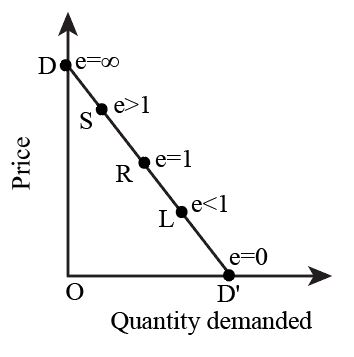

Uniquely, if we look at a linear demand curve, you can see that it gets more and more elastic towards the upper portion of the curve. That’s because a given absolute change in price towards the top of the curve represents a smaller percentage change, making the denominator smaller.

Source: Study.com

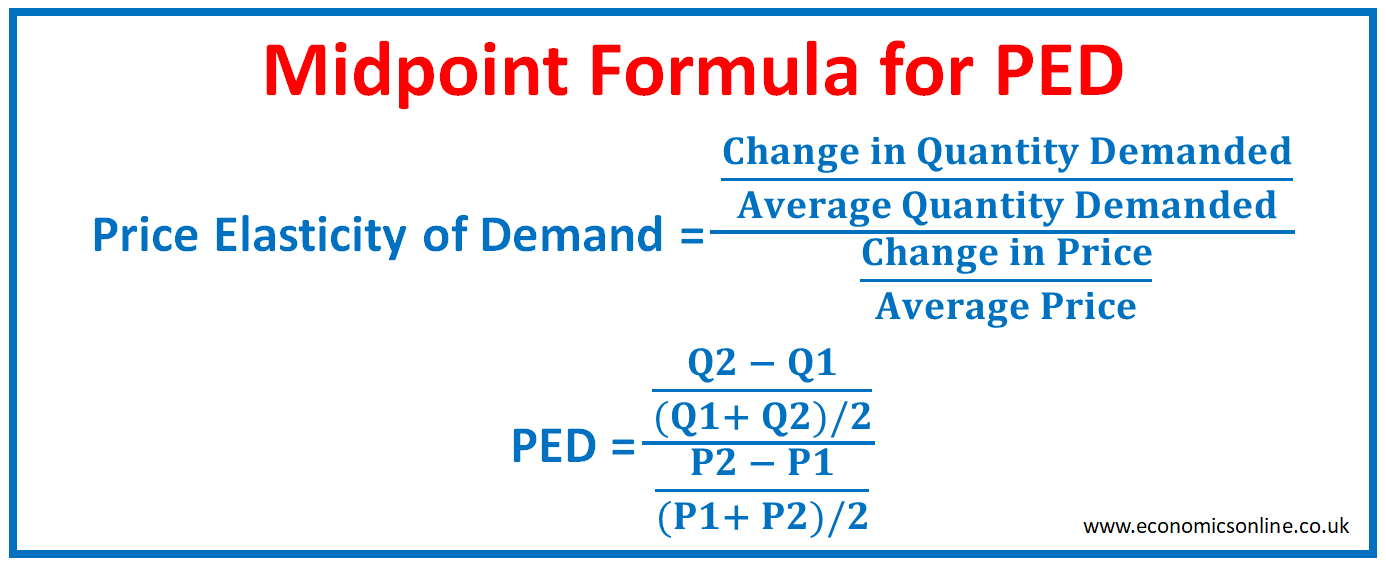

Some people also use the midpoint formula to ensure that the price elasticity between two points is the same regardless of order. It allows us to move up and down the demand curve and get the same value.

Source: Economics Online

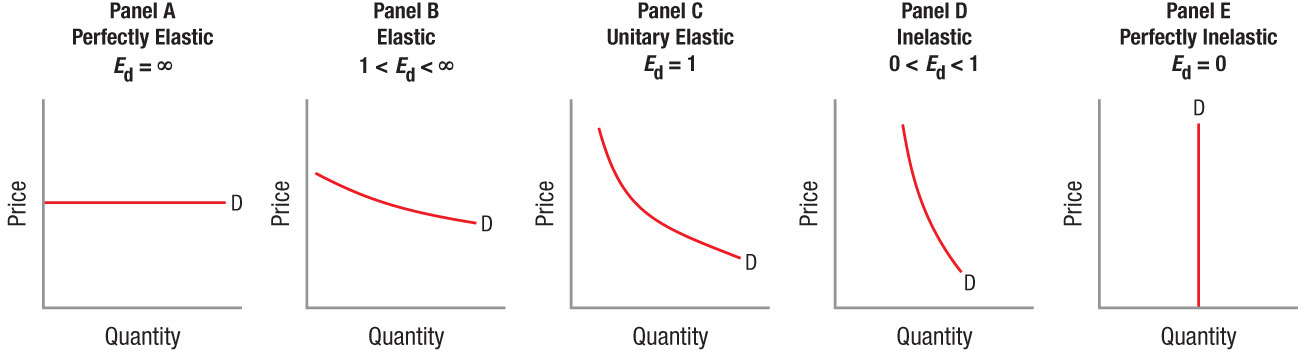

There are some classifications worth memorizing. If elasticity is greater than 1, the demand is elastic. If less than 1, demand is inelastic. If equal to 1, demand is unit elastic. If it’s very elastic, that means it flexes easily; looking back at the formula, to be greater than one, the percent change in quantity must be greater than the percent change in price between two points. Likewise, to be less than one and inelastic, the percent change in price must be greater than the percent change in quantity. In other words, changing the price of something that’s inelastic will drastically change the amount of people who buy it, whereas changing the price of something that’s inelastic won’t have as proportionately large of an impact on quantity.

So what factors determine price elasticity of demand? For starters, there’s substitutes. If there are many substitutes available, demand would be elastic because – if the price is changed even a little bit, people would just find cheaper counterparts. Another aspect is whether the good is a luxury or necessity; if it’s a luxury, people respond to changes in price and demand is therefore elastic. If it’s a necessity, however, people just have to accept the price increases and continue purchasing, to an extent. Take Insulin medication for diabetes patients as an example.

In general, the less expensive a product, the more inelastic is demand. That’s because each absolute change in price is – in terms of percentage – quite large. Also, passage of time makes demand more elastic. That’s because firms change their production to meet new demand, usually resulting in more substitutes being available.

Notice how the shape of the curve is correlated with elasticity.

Source: Digfir

Let’s talk about elasticity’s connection to revenue. Revenue can change in two ways, the first of which is through something called the price effect. The price effect is self-explanatory: as price increases or decreases, each unit is sold at a higher or lower price. But it works in tandem with the quantity effect. The quantity effect states that as price increases or decreases, fewer or more units are sold.

In each case, total revenue is impacted by an increase in price. With elastic demand, increasing price decreases revenue. With inelastic demand, increasing price increases revenue. And with unit-elastic demand, there is no change in revenue following a price increase.