Market Structures

The last topic in this introductory course that we’ll cover is market structures, of which there are four main types: perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition.

Perfect competition is a market structure in which firms are price takers, meaning that the market determines the price. Firms simply accept the determined market price and are only able to sell at that price. There are also no barriers to entry or exit, meaning that nothing is preventing anyone from opening or closing a firm in this market. From the consumer’s point of view, there is no product differentiation in perfect competition; everyone is selling the exact same good. Remember, it’s a “perfect” case; it works in economic theory, but doesn’t actually exist in the real world. The closest example to perfect competition could be the markets for staple crops like wheat and corn.

Based on these conditions, do you think that an individual firm’s demand curve would be highly elastic or inelastic? If you said elastic, you’d be correct. In fact, since there is ZERO product differentiation, individual firms’ demand curves are perfectly elastic – they’re horizontal.

A monopoly is a market where ONE firm controls all outputs and there are no close substitutes available. They have total control of price and market outcomes, and any entry from another firm into the market is blocked. Patents and other forms of intellectual property protection are good examples of restrictive barriers to entry. Sometimes, monopolies are backed by the government; in other cases, they’re heavily regulated against. A natural monopoly is a type of monopoly that undergoes high fixed costs that other firms are unable to go through in order to achieve economies of scale, outcompeting competitors. Public utilities are the standard example here; the investment in infrastructure to build something like an extensive underground water pipeline is huge, but the average cost of production goes down as output increases.

An oligopoly is a market characterized by a few large firms dominating it. There are substantial barriers to entry (but it’s not completely blocked), firms have considerable control over price (not total), and they tend to cooperate strategically (which is where game theory comes into play). A general guideline is the four-firm concentration ratio: a market is an oligopoly if the top four firms in the market control more than 50% of market share. Some examples include the cellphone market (think Apple and Samsung) and the cereal market (think Kellogg's and General Mills).

Monopolistic competition exists when there are a very large number of firms and differentiated products. The important defining characteristic is that there are limited barriers to entry in the long run, meaning that firms can enter and exit with relative ease. Most markets in the real world display monopolistic competition.

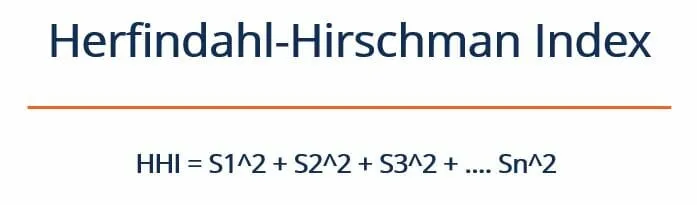

Also take note of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (that’s a mouthful, just use “HHI”), a metric used by many government antitrust agencies to prevent monopolization. The formula for calculating HHI is to square the market share of each firm in an industry and sum it up. In a monopoly, the HHI would be 10,000 since 100^2 = 10,000.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute

A market with an HHI greater than 2,500 is generally considered “highly concentrated.” In the US, mergers and acquisitions between two firms that increase HHI by more than 200 in highly concentrated markets actually get prevented from happening by courts. Still, markets – more than 75% of them – have become more highly concentrated in the last two decades. Whether or not that matters is up to you to decide – it really depends on the school of thought. Some argue that concentration is a result of meaningful innovation that is valuable to consumers, while others have found that concentration results in massive price increases.