Protectionism

We’ve seen how trade can be highly beneficial for countries; it allows them to consume outside of their PPC and maximize the value of production. However, it can also have negative impacts, like leading to the loss of domestic jobs and building an over-reliant economy that is prone to external shocks from other countries. In trying to mitigate these negative impacts, countries employ something called protectionism, the idea of using policy to protect (as the name suggests) domestic industries.

In a market with trade, the upward sloping domestic supply curve and downward sloping domestic demand curve remain. But one more curve is added: a horizontal foreign supply curve. It’s horizontal because it assumes that we can import as much as possible from the rest of the world at an international equilibrium price.

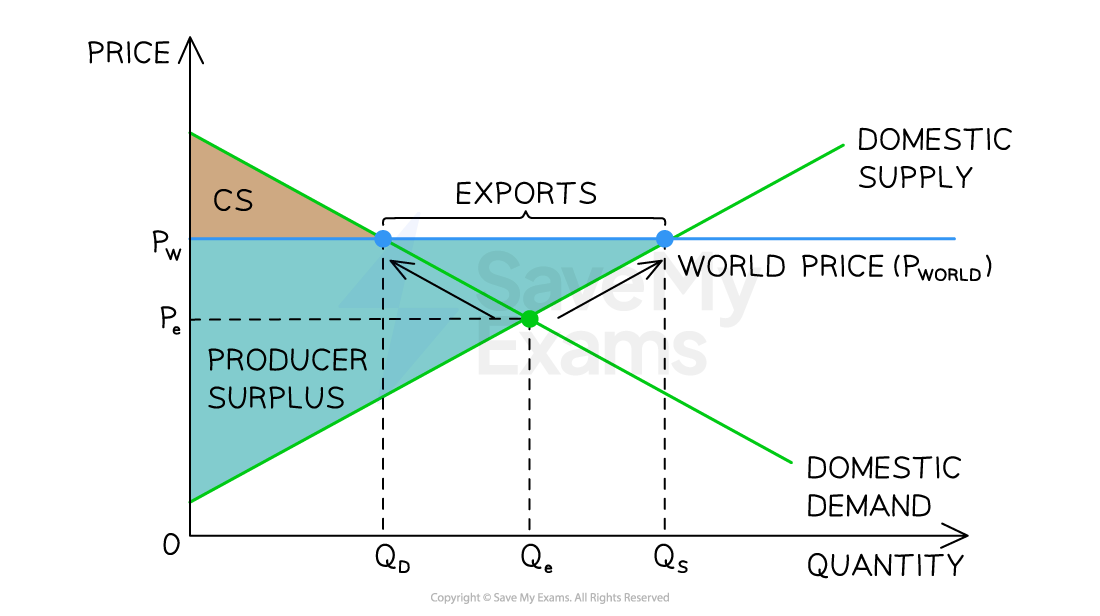

Source: SaveMyExams

In this image, the world price is above the domestic price. Notice how the result is an increase in producer surplus and a decrease in consumer surplus. Logically, it makes sense: if the price of buying the good from another country is much higher, domestic producers can charge higher prices because domestic consumers have nowhere else to buy the good from. Dealing with these prices, consumers lose value and their surplus decreases. Moreover, notice that the difference between quantity supplied and quantity demanded gets exported to other countries, increasing producer surplus not just through domestic transactions but also foreign ones. The reasoning behind the exports is that foreign consumers are willing to pay a higher price, meaning that there’s an incentive for domestic producers to enter that market – per the law of supply.

When world price is below equilibrium, the graph is the opposite. Producer surplus decreases, consumer surplus increases. Instead of exports, there are imports. It’s in this scenario that domestic policymakers consider the tariff, a tax on imported goods. It restores producer surplus by taxing imported goods. One issue, though, is that other countries may retaliate by placing tariffs on our goods, which can escalate into a “tariff war,” a term you might’ve heard on the news lately. Let’s see what it looks like on the graph:

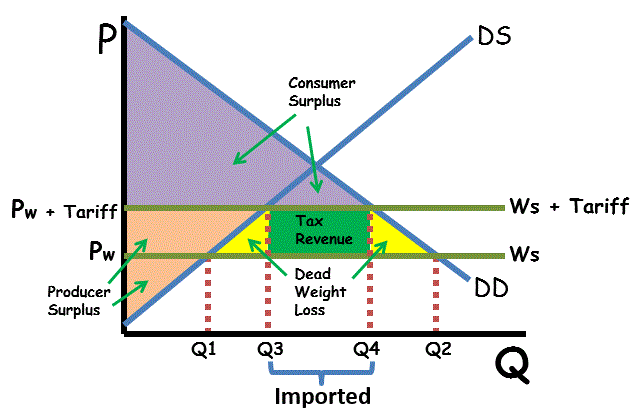

Source: ReviewEcon

The world supply after the tariff is shifted to the left; in this case, it is technically shifted upward because world supply is horizontal. Notice how the tariff restores some of the lost producer surplus while also creating tax revenue (green rectangle) and DWL (yellow triangles). Notably, this tariff has made the cost of importing high, but not so high that all imports stop. The quantity Q4 - Q3 continues to be imported, but consumer surplus is certainly lesser than it was before the tariff.

Import quotas are another protectionist policy; they limit the amount of a good that can be imported. Like tariffs, they also result in increased prices for domestic consumers. Unlike tariffs, though, they don’t contribute to government revenue. Again, the takeaway is that domestic producer surplus and production increase, while consumer surplus decreases.